drtbear1967

Musclechemistry Board Certified Member

<header class="entry-header">How to Squat

<time class="entry-time" itemprop="datePublished" datetime="2017-06-21T10:26:58+00:00">June 21, 2017</time> by Nia Shanks

</header>

Everyone should train the squat movement, in some form.

Everyone should train the squat movement, in some form.

The squat movement is as functional as exercise can get. You squat to sit in a chair or get in, and out of, a vehicle. You squat to the toilet. You squat to do lots of things. Like the book Everybody Poops – well, everybody squats.

It’s a basic human movement pattern – one that can be trained, loaded, and progressed in numerous ways. When used in a progressive strength training program the squat is useful for getting stronger, building muscle, losing fat, becoming more awesome, improving quality of life, and testing your mental fortitude.

Basically, unless you have a physical limitation, there’s no reason not to squat.

I’ll demonstrate 3 popular loaded squat variations below and discuss the advantages and limitations of each.

Goblet Squat

Goblet squats are my favorite variation for those who are new to strength training because this variation can be learned quickly and has a smaller learning curve than, say, a barbell squat. Because this variation can be learned quickly, it builds training confidence. This is also a terrific squat variation for someone who is intimidated by strength training with a barbell (not everyone is comfortable putting a bar on their back the first time they strength train). And it’s a great squat variation for someone who doesn’t have access to a barbell and squat stands/power cage.

Here’s a video that demonstrates how to properly perform goblet squats.

<iframe id="fitvid511226" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/9Dqet845KY0?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

The goblet squat is a great way to load and progress the squat movement, but it has a big limitation: loading potential. You can only hoist and hold a certain amount of weight in that position. There will come a point when you can’t hold a heavier weight and the only option to improve performance will be performing more reps, more sets, or increasing workout density (i.e., doing the same amount of work in less time).

But I like getting stronger by adding more weight, and that’s why I recommend trainees transition to barbell squats.

Before we get to barbell back squats, there’s another squat variation some trainees may prefer to progress to after the goblet squat.

Landmine Squat

Ben Bruno has popularized this squat variation, and I consider it a beefed-up version of the goblet squat, due to the placement of the load.

For someone who prefers the goblet squat variation over a barbell squat, this a good option because it allows for heavier loading than a goblet squat.

<iframe id="fitvid8536" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/X0lRwV368HI?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

The main limitation to this movement is the necessity of a “landmine” tool (I’m using a post landmine in the video), or jamming the end of a barbell into a corner padded with a rolled-up towel (some gyms may not appreciate this). And, like the goblet squat, getting the weight into position can be awkward if you can’t elevate the barbell so it’s easier to get into position, as discussed in the video.

Another limitation of the landmine squat: it reduces the balance demand. Since the barbell is in a somewhat-fixed path of motion and you lean into the bar, you don’t have to balance and stabilize to the extent demanded by a goblet and barbell squat.

Some people love the feel of this squatting pattern so, again, individual preferences play a role.

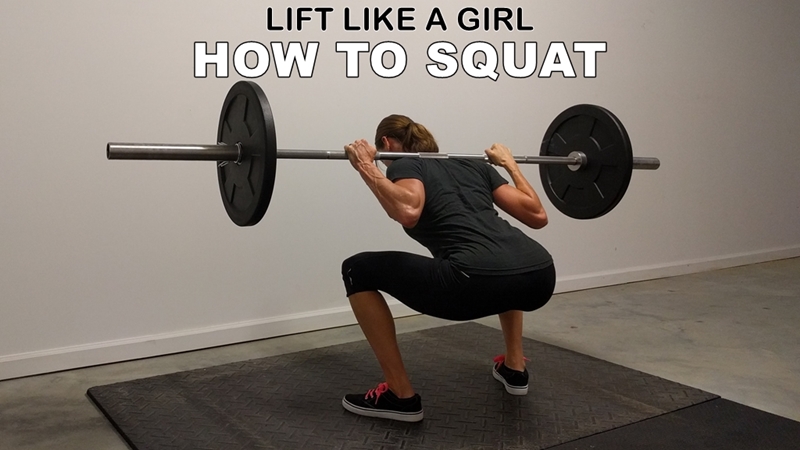

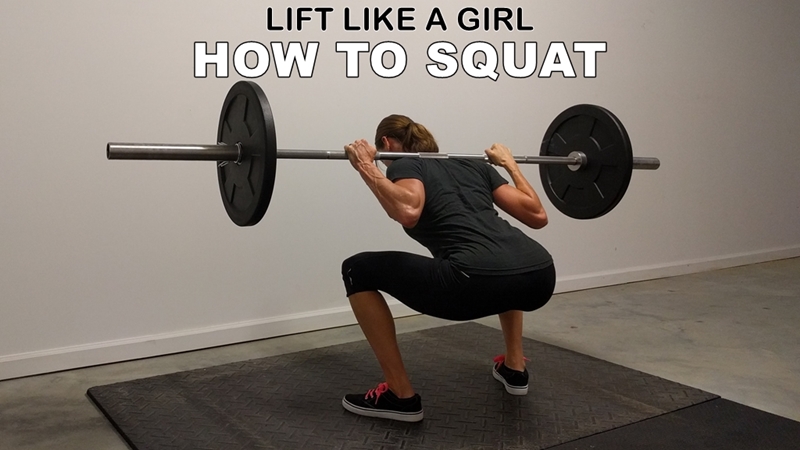

Barbell Squat

The greatest advantage of the barbell squat is the loading potential; it allows for far more weight to be added over time than a goblet or landmine squat. (I’ve see plenty of women crush 200+ and 300+ pound barbell squats, but I’ve never seen one lift that amount with a goblet or landmine variation.)

Most dumbbells, and many kettlebells, increase in 5-pound increments. But you can use fractional plates with barbell exercises. They allow a mere half-pound to be added to the bar. These smaller increases allow for longer progress to be made for a given rep range.

For example, if I told you to perform 4 sets of 6 reps with goblet squats and to increase the weight every time you performed the workout, how long could you progress, assuming the smallest weight increase is 5 pounds? You may start out with a 20-pound dumbbell, but adding 5 pounds each workout may lead to a quick stall out.

Contrast that with a barbell squat with the same guidelines: add weight each time and perform 4 sets of 6 reps. You’d very likely be able to add 5 pounds each workout for several weeks (because this exercise allows you to use more weight than a goblet squat anyway), but once a 5-pound jump felt like too much, you could use fractional plates and add 2 pounds, or just 1 pound, to the bar each time.

It’s also easier to get the bar into position for a barbell squat than the goblet and landmine variations, and a barbell squat demands more stabilization and balance than the landmine squat.

<iframe id="fitvid525522" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/S5Qxt7eXqsc?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

As with any exercise, the squat has its potential limitations.

Someone with shoulder mobility issues, or an old injury that prevents them from holding a barbell on their back, may not be able to perform the movement (this is when another variation like front squats or safety bar squats could work well – these are discussed below).

You also have to be confident as the weight gets heavier. Not every woman (or man) likes the feel of a heavy bar on her back. Not everyone is comfortable squatting without a spotter, and some don’t have a power rack with safety bars to squat in. Barbell squats demand a certain level of confidence and fortitude.

Common Squat Mistakes And How to Correct Them

Usually (read, not always) someone who claims barbell squats hurt is doing something incorrectly. As the saying goes: squatting doesn’t hurt, squatting incorrectly hurts.

If you’re an individual who experiences discomfort or pain with squatting, the reason could simply be a form issue.* This video explains:

<iframe id="fitvid799226" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/n0LgOywoZC8?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

Apply the cues and suggestions to your squats and see how it feels.

*Not everyone who experiences pain when squatting with a barbell is doing the movement incorrectly. If your form is not the issue and pain persists, go see a physical therapist (preferably one with strength training experience) to determine the cause.

Which Variation to Start With?

This depends on the individual, but I tend to start beginners with goblet squats, unless they request to start with a barbell. Once they’ve nailed the squatting movement, increased the weight used for goblet squats, and built training confidence I transition them to barbell squatting.

For trainees who don’t have a barbell or simply don’t want to squat with a barbell, the landmine variation can be used to allow for additional loading not afforded by the goblet variation.

Other Squat Variations

There are other great squat variations in addition to those provided above:

Double dumbbell/kettebell squat (with a ‘bell held at each shoulder) – this is another good variation but, again, is limited by the amount of weight you can get into position. This is a great variation if you only have dumbbells or kettlebells to train with.

Front squat – I really like front squats and would consider transitioning to them from goblet squats. But many women find them incredibly uncomfortable (because they don’t have as much muscle mass on the upper body as men, so the bar may end up resting on the clavicles; some despise having something touch their throat, too) and don’t stick with them for long. If you find back squats don’t agree with you or cause pain/discomfort, try front squats. Most people seem to be able to perform these without any issues (except for the inevitable discomfort of the bar placement).

Safety squat – This is my go-to variation for those with shoulder mobility issues, or shoulder injuries that prevent the use of back squats. It requires a specialty bar, but it’s a terrific option.

Low bar squat –The low bar variation, widely used in powerlifting, potentially allows for heavier loading because the bar is set lower on the back (below the spine of the scapulae). And, when performed the way Mark Rippetoe instructs in Starting Strength, uses hip drive when coming up out of the bottom position. If you’re interested in lifting maximum weight, this is a great variation to include. The potential drawbacks for some people: it can be uncomfortable because of where the bar sits, and for some trainees the bar placement can be hard on the elbows and shoulders.

Start Squatting

Squats are undeniably one of the best movements you can include in a strength training program, especially if you’re goal is efficiency. If you’re interested in using the fewest exercises per workout that provide the greatest results, squats make the cut every time.

<time class="entry-time" itemprop="datePublished" datetime="2017-06-21T10:26:58+00:00">June 21, 2017</time> by Nia Shanks

</header>

The squat movement is as functional as exercise can get. You squat to sit in a chair or get in, and out of, a vehicle. You squat to the toilet. You squat to do lots of things. Like the book Everybody Poops – well, everybody squats.

It’s a basic human movement pattern – one that can be trained, loaded, and progressed in numerous ways. When used in a progressive strength training program the squat is useful for getting stronger, building muscle, losing fat, becoming more awesome, improving quality of life, and testing your mental fortitude.

Basically, unless you have a physical limitation, there’s no reason not to squat.

I’ll demonstrate 3 popular loaded squat variations below and discuss the advantages and limitations of each.

Goblet Squat

Goblet squats are my favorite variation for those who are new to strength training because this variation can be learned quickly and has a smaller learning curve than, say, a barbell squat. Because this variation can be learned quickly, it builds training confidence. This is also a terrific squat variation for someone who is intimidated by strength training with a barbell (not everyone is comfortable putting a bar on their back the first time they strength train). And it’s a great squat variation for someone who doesn’t have access to a barbell and squat stands/power cage.

Here’s a video that demonstrates how to properly perform goblet squats.

<iframe id="fitvid511226" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/9Dqet845KY0?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

The goblet squat is a great way to load and progress the squat movement, but it has a big limitation: loading potential. You can only hoist and hold a certain amount of weight in that position. There will come a point when you can’t hold a heavier weight and the only option to improve performance will be performing more reps, more sets, or increasing workout density (i.e., doing the same amount of work in less time).

But I like getting stronger by adding more weight, and that’s why I recommend trainees transition to barbell squats.

Before we get to barbell back squats, there’s another squat variation some trainees may prefer to progress to after the goblet squat.

Landmine Squat

Ben Bruno has popularized this squat variation, and I consider it a beefed-up version of the goblet squat, due to the placement of the load.

For someone who prefers the goblet squat variation over a barbell squat, this a good option because it allows for heavier loading than a goblet squat.

<iframe id="fitvid8536" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/X0lRwV368HI?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

The main limitation to this movement is the necessity of a “landmine” tool (I’m using a post landmine in the video), or jamming the end of a barbell into a corner padded with a rolled-up towel (some gyms may not appreciate this). And, like the goblet squat, getting the weight into position can be awkward if you can’t elevate the barbell so it’s easier to get into position, as discussed in the video.

Another limitation of the landmine squat: it reduces the balance demand. Since the barbell is in a somewhat-fixed path of motion and you lean into the bar, you don’t have to balance and stabilize to the extent demanded by a goblet and barbell squat.

Some people love the feel of this squatting pattern so, again, individual preferences play a role.

Barbell Squat

The greatest advantage of the barbell squat is the loading potential; it allows for far more weight to be added over time than a goblet or landmine squat. (I’ve see plenty of women crush 200+ and 300+ pound barbell squats, but I’ve never seen one lift that amount with a goblet or landmine variation.)

Most dumbbells, and many kettlebells, increase in 5-pound increments. But you can use fractional plates with barbell exercises. They allow a mere half-pound to be added to the bar. These smaller increases allow for longer progress to be made for a given rep range.

For example, if I told you to perform 4 sets of 6 reps with goblet squats and to increase the weight every time you performed the workout, how long could you progress, assuming the smallest weight increase is 5 pounds? You may start out with a 20-pound dumbbell, but adding 5 pounds each workout may lead to a quick stall out.

Contrast that with a barbell squat with the same guidelines: add weight each time and perform 4 sets of 6 reps. You’d very likely be able to add 5 pounds each workout for several weeks (because this exercise allows you to use more weight than a goblet squat anyway), but once a 5-pound jump felt like too much, you could use fractional plates and add 2 pounds, or just 1 pound, to the bar each time.

It’s also easier to get the bar into position for a barbell squat than the goblet and landmine variations, and a barbell squat demands more stabilization and balance than the landmine squat.

<iframe id="fitvid525522" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/S5Qxt7eXqsc?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

As with any exercise, the squat has its potential limitations.

Someone with shoulder mobility issues, or an old injury that prevents them from holding a barbell on their back, may not be able to perform the movement (this is when another variation like front squats or safety bar squats could work well – these are discussed below).

You also have to be confident as the weight gets heavier. Not every woman (or man) likes the feel of a heavy bar on her back. Not everyone is comfortable squatting without a spotter, and some don’t have a power rack with safety bars to squat in. Barbell squats demand a certain level of confidence and fortitude.

Common Squat Mistakes And How to Correct Them

Usually (read, not always) someone who claims barbell squats hurt is doing something incorrectly. As the saying goes: squatting doesn’t hurt, squatting incorrectly hurts.

If you’re an individual who experiences discomfort or pain with squatting, the reason could simply be a form issue.* This video explains:

<iframe id="fitvid799226" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/n0LgOywoZC8?feature=oembed" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

Apply the cues and suggestions to your squats and see how it feels.

*Not everyone who experiences pain when squatting with a barbell is doing the movement incorrectly. If your form is not the issue and pain persists, go see a physical therapist (preferably one with strength training experience) to determine the cause.

Which Variation to Start With?

This depends on the individual, but I tend to start beginners with goblet squats, unless they request to start with a barbell. Once they’ve nailed the squatting movement, increased the weight used for goblet squats, and built training confidence I transition them to barbell squatting.

For trainees who don’t have a barbell or simply don’t want to squat with a barbell, the landmine variation can be used to allow for additional loading not afforded by the goblet variation.

Other Squat Variations

There are other great squat variations in addition to those provided above:

Double dumbbell/kettebell squat (with a ‘bell held at each shoulder) – this is another good variation but, again, is limited by the amount of weight you can get into position. This is a great variation if you only have dumbbells or kettlebells to train with.

Front squat – I really like front squats and would consider transitioning to them from goblet squats. But many women find them incredibly uncomfortable (because they don’t have as much muscle mass on the upper body as men, so the bar may end up resting on the clavicles; some despise having something touch their throat, too) and don’t stick with them for long. If you find back squats don’t agree with you or cause pain/discomfort, try front squats. Most people seem to be able to perform these without any issues (except for the inevitable discomfort of the bar placement).

Safety squat – This is my go-to variation for those with shoulder mobility issues, or shoulder injuries that prevent the use of back squats. It requires a specialty bar, but it’s a terrific option.

Low bar squat –The low bar variation, widely used in powerlifting, potentially allows for heavier loading because the bar is set lower on the back (below the spine of the scapulae). And, when performed the way Mark Rippetoe instructs in Starting Strength, uses hip drive when coming up out of the bottom position. If you’re interested in lifting maximum weight, this is a great variation to include. The potential drawbacks for some people: it can be uncomfortable because of where the bar sits, and for some trainees the bar placement can be hard on the elbows and shoulders.

Start Squatting

Squats are undeniably one of the best movements you can include in a strength training program, especially if you’re goal is efficiency. If you’re interested in using the fewest exercises per workout that provide the greatest results, squats make the cut every time.

Last edited: