What is the thermic effect of food and can it help you lose weight? Find out in this article.

The post How to Use the Thermic Effect of Food to Boost Your Metabolism appeared first on Legion Athletics.

[h=2]Key Takeaways[/h]

Imagine, for a second, that you could lose weight faster by simply eating the right foods. Or, simply changing your meal schedule.

You know . . .

The reality is no food can directly cause fat loss.

(Some foods are more conducive to fat loss than others, but that’s not the same as causing fat loss. More on this soon.)

“What about foods that boost your metabolism, though?” you might be thinking.

And that’s what brings us to the topic of this article: the thermic effect of food.

Fitness magazines and “miracle diet” hucksters claim that eating foods with a high thermic effect is the secret to getting the body of your dreams.

If only it were that simple.

The thermic effect of food does play a role in your metabolism and weight loss and weight gain, but not in the way that many people would have you believe.

That is, the foods you eat do affect your metabolism and the speed at which you lose or gain weight, but they aren’t the primary determinants.

And in this article, we’re going to break it all down.

By the end, you’re going to know what the thermic effect of food is and several science-based ways to use it to help improve your metabolism and achieve your fitness goals.

[h=2]What Is the Thermic Effect of Food?[/h]

The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the amount of energy required to digest and process the food you eat.

It’s also referred to as specific dynamic action (SDA) and dietary induced thermogenesis (DIT), and research shows that it accounts for approximately 10% of your total daily energy expenditure.

Generally, TEF is measured as a percentage of the calories of a food that are required to digest that food. In other words, if a portion of a particular food contains 100 calories, and the body burns 20 calories to digest it, that food has a TEF of 20% (20 / 100 = 20%).

In this way, your metabolism does speed up when you eat, and the amount depends on three factors:

Read: How Bad Is Alcohol for You, Really?

After macronutrient composition, the second major determinant of TEF is the level of processing a food has undergone—foods that are more processed have a lower TEF than foods that are less processed.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Pomona College found a processed-food meal of white bread and American cheese increased TEF about 10%, whereas a whole-food meal of multi-grain bread and cheddar cheese increased TEF about 20%. The difference would likely be even higher if the subjects ate a meal of high-fiber vegetables and lean protein (which is even less processed than multi-grain bread and cheddar cheese).

Finally, how much food you eat in one sitting also affects your post-meal TEF, with larger meals causing a bigger increase than smaller ones.

Now, if we left the discussion at that, you would probably walk away with the same misconception that many people have:

If different foods boost your metabolism more than others, then you can lose weight simply by eating large amounts of high-TEF foods.

Well, as much as I wish merely eating food was a viable fat loss strategy, it’s not.

And to understand why, we need to dive deeper into what really happens when you eat and how it relates to fat burning . . .

Success! Your coupon is on the way. Keep an eye on that inbox!

Looks like you're already subscribed!

[h=2]How Does the Thermic Effect of Food Relate to Your Metabolism?[/h]When you eat food, energy expenditure rises, which is good for fat loss.

What’s bad for fat loss, though, is that after eating a meal . . .

To understand why, let’s look at exactly what happens when we eat.

Digestion starts as soon as you put food into your mouth.

Enzymes in your saliva begin breaking down food as it moves toward the stomach, which takes over the process of reducing food to usable nutrients.

Protein becomes amino acids, carbs become glucose and glycogen, dietary fat becomes fatty acids, and so on.

Read: What Every Weightlifter Should Know About Glycogen

Next up is the small intestine, which continues to digest food into nutrients and then absorbs those nutrients into the blood.

Once the nutrients have passed through the walls of the small intestine and into the bloodstream, they need to be transported into cells for use.

And this is where the hormone insulin comes into play.

As well as shuttling nutrients into cells, insulin inhibits lipolysis (the breakdown of fat cells for energy) and stimulates lipogenesis (the storage of calories in fat cells). It also shuttles nutrients into fat cells whose job is to, well, get fatter.

This makes sense because why should your body burn fat for energy when it has an abundance of food energy (calories) available?

That might sound bad, but realize that if your body were unable to continually replenish its fat stores, they would slowly (or quickly, depending on how active you are) shrink until you eventually died.

Read: “Metabolic Damage” and “Starvation Mode,” Debunked by Science

These mechanisms are why many “gurus” vilify insulin and eating carbs (because carbs spike insulin levels).

As insulin blunts fat burning and triggers fat storage, the basic theory is the more insulinogenic a diet is, the more it will cause weight gain.

This seems plausible at first blush, but it completely ignores the most important dimension of weight management:

Energy intake.

Because the reality is insulin can’t make you fat. Only overeating can.

Read: Research Review: Are Ketogenic Diets Best for Fat Loss?

The scientific underpinnings at play here are referred to as energy balance, which is the relationship between the amount of energy you expend (burn) and consume (eat).

You can get fatter eating only the “cleanest” fare and lose fat on a diet of convenience store pigswill.

These principles don’t just apply to your diet as a whole and over time—they apply to every meal you eat.

Specifically, your body is always in one of two states in relation to food:

A “fed” state.

In this state, your body is digesting, processing, absorbing, and storing nutrients from food you’ve eaten. This is when fat burning is blunted and fat stores are increased.

A “fasted” state.

In this state, your body has finished processing and absorbing (and storing) food you’ve eaten. This is when it must turn to its fat stores to obtain the energy necessary to stay alive, and hence when fat stores are decreased.

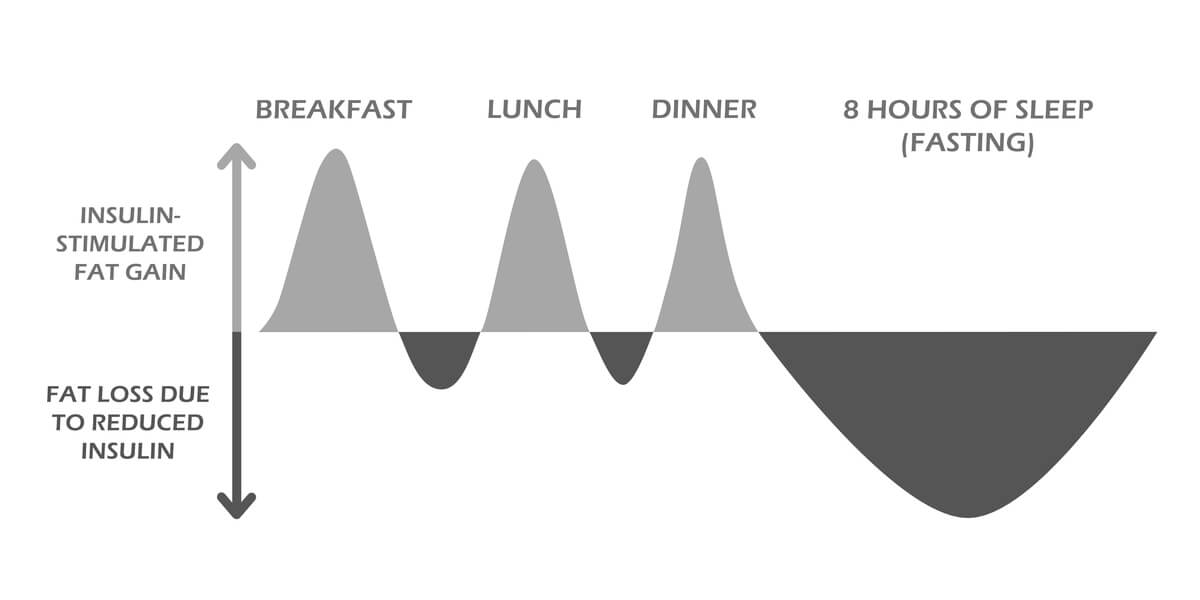

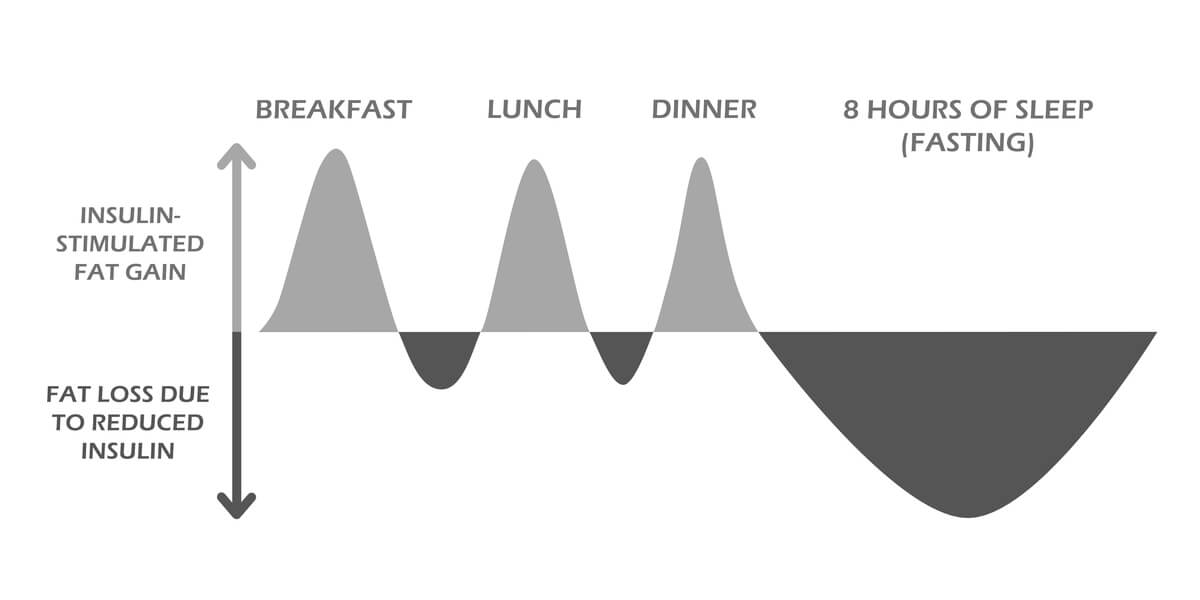

In other words, your body alternates between storing and burning fat every day, which is neatly illustrated by the following graph:

If you take a closer look at that graph, you can come to a few simple conclusions:

We recall that TEF contributes to overall energy expenditure, which means it slightly decreases the size of the green areas of the graph (the post-meal fat storage).

That is, TEF can contribute to weight loss by increasing the amount of energy your body burns, but the magnitude of these effects is far too small to really move the needle.

You can gain weight on a diet rich in high-TEF foods because you simply eat too much of them, and you can lose weight on a diet rich in low-TEF foods because you simply know how many calories to eat and regulate your intake of them.

This is why the entire idea of “fat-burning foods” is a myth.

Fitness blogs can write all the listicles they want about which foods burn fat and which don’t, but it’s all a bunch of humbug.

It doesn’t matter how much celery or tuna you eat every day—it’s not going to noticeably decrease your fat stores unless you’re also in a state of negative energy balance (a calorie deficit).

And you now know why:

Food doesn’t burn fat. Energy expenditure does.

Thanks to TEF and other factors beyond the scope of this article, some foods result in less fat storage than others, but rest assured that an energy surplus results in some degree of fat gain regardless of the composition of your diet.

I mentioned earlier that some foods are more conducive to weight loss than others.

That is, they’re not “fat-burning foods,” but they do help you lose weight faster.

Generally speaking, foods that are “good” for weight loss are those that are relatively low in calories but high in volume (and thus satiating).

Many also have a high TEF value as well, and that’s an added bonus.

Examples of such foods include . . .

Remember that foods with minimal processing tend to have the highest thermic effect, and this is true of proteins, carbs, and fats, so you want to prioritize these in your diet to maximize TEF.

[h=3]Protein[/h]Most high-protein foods will have a thermic effect of anywhere from 20 to 35%—meaning they’re highly thermogenic. Here are some proteins with a high thermic effect:

If eating food boosts your metabolism, eating more meals should be better than fewer . . . right?

Wrong.

The flaw in this logic is the assumption that all meals result in more or less the same increase in energy expenditure.

The reality, though, is small meals result in smaller, shorter metabolic spikes, and larger meals produce larger, longer lasting effects.

And is there any benefit to one of these over the other?

That is, does eating fewer, larger meals raise your total daily TEF more than eating more frequent, smaller meals, or vice versa?

Maybe, but probably not.

Some studies show that eating fewer, large meals raises total daily TEF more than eating more frequent, smaller meals. That said, all of these studies were fairly short, didn’t involve many participants, and didn’t track body weight over time, so it’s impossible to say one method is clearly better than the other.

What’s more, many studies have shown that there’s no significant difference in total energy expenditure between “nibbling” and “gorging.”

In other words, your total daily TEF balances out to more or less the same amount regardless of how many meals you eat or how often you eat them.

Thus, the best approach is to follow the meal frequency that works best for you.

If you prefer to eat more frequent, smaller meals, go for it—and if you prefer to eat less frequent, larger meals, that’s fine, too.

The most important thing is that you follow a meal frequency that you enjoy and that helps you reliably meet your daily calorie and macronutrient targets.

Yes, probably.

First, at least one study has shown that strength training can boost TEF considerably. Specifically, people who ate a 660-calorie meal experienced a 20% increase in TEF over the next two hours, whereas people who ate the same meal after lifting weights enjoyed a 34% increase in TEF—a 73% (relative) increase!

Research also shows that the lower your insulin sensitivity and the higher your body fat percentage, the lower your TEF will be. Thus, it’s possible that the reverse is also true—that improving your insulin sensitivity and reducing your body fat levels may increase your TEF.

Now, it’s still not clear if being insulin sensitive and lean causes an increase in TEF or if it’s just correlated with a high TEF (people who are lean and insulin sensitive might just happen to have a higher TEF, for example). But it’s one of the few things you might be able to do to raise TEF, so it’s worth trying (not to mention the fact that being insulin sensitive and lean confers a number of other benefits).

Read: 13 Studies Answer: What’s the Best Way to Lower Blood Sugar?

There’s nothing you can do to automagically boost your insulin sensitivity or reduce your body fat percentage, but you can improve both significantly by exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet.

So, if you want to increase the amount of energy your body uses to digest food, the best way to do so is by doing a few hours of strength training and cardio each week, and eat a calorie-controlled and nutritious diet.

And that’s the reality that while TEF isn’t terribly important in the overall scheme of losing fat, the best type of diet for weight loss is highly thermogenic.

We recall that protein, carbs, and fats affect the metabolism in different ways. They have different TEF values and they are processed and stored differently.

For example, high-protein and high-carb meals cause a bigger metabolic boost and result in less immediate fat storage than high-fat meals.

It’s not surprising, then, to learn that research shows that high-protein, high-carb diets (which are highly thermogenic) are best for maximizing fat loss.

There are several reasons for this:

If you’re healthy and physically active, a high-protein, moderate-to-high-carb, and moderate-to-low-fat intake is generally going to be best.

(If that sounds ludicrous to you, check out this article on the big myths surrounding low-carb and high-fat dieting.)

That said, getting a larger portion of your daily calories from foods that have a higher TEF like minimally processed lean proteins, vegetables, and whole grains can make it slightly easier to lose weight and keep it off.

What’s more, there’s good evidence that strength training can also amplify the thermic effect of food.

Practically speaking, though, your primary concern when trying to lose weight should be meeting your daily calorie and macronutrient targets and eating a plant-centric, whole foods diet. Luckily, this kind of diet also happens to be highly thermogenic.

In other words, when you eat a high-protein, moderate-to-high-carb, and moderate-to-low-fat diet made up of mostly whole foods, you’re going to reap all the benefits of the thermic effect of food automatically.

One more reason to focus on the fundamentals.

If you liked this article, please share it on Facebook, Twitter, or wherever you like to hang out online!

[h=3]What’s your take on the thermic effect of food? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below![/h]The post How to Use the Thermic Effect of Food to Boost Your Metabolism appeared first on Legion Athletics.

{feed:enclosure_href }

More...

The post How to Use the Thermic Effect of Food to Boost Your Metabolism appeared first on Legion Athletics.

[h=2]Key Takeaways[/h]

- The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the amount of energy required to digest and process the food you eat.

- You can increase your daily TEF by eating more protein and whole foods, but increasing your meal frequency or size will not (eating more often won’t “boost” your metabolism).

- Keep reading to learn how the thermic effect of food works, the foods with the highest thermic effect, how to boost the thermic effect of food, and more!

Imagine, for a second, that you could lose weight faster by simply eating the right foods. Or, simply changing your meal schedule.

You know . . .

- Your morning grapefruit slims and trims your thighs.

- Your daily lunch of canned tuna chips away at your belly fat.

- Your habit of “nibbling” on small meals every few hours keeps fat loss humming along throughout the day.

The reality is no food can directly cause fat loss.

(Some foods are more conducive to fat loss than others, but that’s not the same as causing fat loss. More on this soon.)

“What about foods that boost your metabolism, though?” you might be thinking.

And that’s what brings us to the topic of this article: the thermic effect of food.

Fitness magazines and “miracle diet” hucksters claim that eating foods with a high thermic effect is the secret to getting the body of your dreams.

If only it were that simple.

The thermic effect of food does play a role in your metabolism and weight loss and weight gain, but not in the way that many people would have you believe.

That is, the foods you eat do affect your metabolism and the speed at which you lose or gain weight, but they aren’t the primary determinants.

And in this article, we’re going to break it all down.

By the end, you’re going to know what the thermic effect of food is and several science-based ways to use it to help improve your metabolism and achieve your fitness goals.

- [h=4]Table of Contents[/h]

- What Is the Thermic Effect of Food?

- How Does the Thermic Effect of Food Relate to Your Metabolism?

- The Great “Fat-Burning Food” Hoax

- 40 Foods with a High Thermic Effect

- Protein

- Carbohydrates

- Vegetables

- Fats

- Will Eating More Frequently Help You Lose Weight Faster?

- Can You Do Anything to Raise the Thermic Effect of Food?

- The True Benefits of a Highly Thermogenic Diet

- The Bottom Line on the Thermic Effect of Food

[h=2]What Is the Thermic Effect of Food?[/h]

The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the amount of energy required to digest and process the food you eat.

It’s also referred to as specific dynamic action (SDA) and dietary induced thermogenesis (DIT), and research shows that it accounts for approximately 10% of your total daily energy expenditure.

Generally, TEF is measured as a percentage of the calories of a food that are required to digest that food. In other words, if a portion of a particular food contains 100 calories, and the body burns 20 calories to digest it, that food has a TEF of 20% (20 / 100 = 20%).

In this way, your metabolism does speed up when you eat, and the amount depends on three factors:

- The macronutrient composition of your meal

- The level of processing the food has undergone

- How much you eat in a meal

- Protein tops the list with a TEF of around 20 to 35%.

- Carbs are next with a TEF of around 5 to 10%.

- And fat is last a TEF of about 0 to 3%.

Read: How Bad Is Alcohol for You, Really?

After macronutrient composition, the second major determinant of TEF is the level of processing a food has undergone—foods that are more processed have a lower TEF than foods that are less processed.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Pomona College found a processed-food meal of white bread and American cheese increased TEF about 10%, whereas a whole-food meal of multi-grain bread and cheddar cheese increased TEF about 20%. The difference would likely be even higher if the subjects ate a meal of high-fiber vegetables and lean protein (which is even less processed than multi-grain bread and cheddar cheese).

Finally, how much food you eat in one sitting also affects your post-meal TEF, with larger meals causing a bigger increase than smaller ones.

Now, if we left the discussion at that, you would probably walk away with the same misconception that many people have:

If different foods boost your metabolism more than others, then you can lose weight simply by eating large amounts of high-TEF foods.

Well, as much as I wish merely eating food was a viable fat loss strategy, it’s not.

And to understand why, we need to dive deeper into what really happens when you eat and how it relates to fat burning . . .

Summary: The thermic effect of food is the amount of energy required to digest and process the food you eat, and the main determinants of TEF are the macronutrient composition of the meal, how processed the foods are, and the size of your meal.

[h=2]Want to save 20% on your first order of Legion supplements?[/h] Sending...

Success! Your coupon is on the way. Keep an eye on that inbox!

Looks like you're already subscribed!

[h=2]How Does the Thermic Effect of Food Relate to Your Metabolism?[/h]When you eat food, energy expenditure rises, which is good for fat loss.

What’s bad for fat loss, though, is that after eating a meal . . .

- Fat burning mechanisms in the body are reduced.

- Fat storage mechanisms in the body are enhanced.

To understand why, let’s look at exactly what happens when we eat.

Digestion starts as soon as you put food into your mouth.

Enzymes in your saliva begin breaking down food as it moves toward the stomach, which takes over the process of reducing food to usable nutrients.

Protein becomes amino acids, carbs become glucose and glycogen, dietary fat becomes fatty acids, and so on.

Read: What Every Weightlifter Should Know About Glycogen

Next up is the small intestine, which continues to digest food into nutrients and then absorbs those nutrients into the blood.

Once the nutrients have passed through the walls of the small intestine and into the bloodstream, they need to be transported into cells for use.

And this is where the hormone insulin comes into play.

As well as shuttling nutrients into cells, insulin inhibits lipolysis (the breakdown of fat cells for energy) and stimulates lipogenesis (the storage of calories in fat cells). It also shuttles nutrients into fat cells whose job is to, well, get fatter.

This makes sense because why should your body burn fat for energy when it has an abundance of food energy (calories) available?

That might sound bad, but realize that if your body were unable to continually replenish its fat stores, they would slowly (or quickly, depending on how active you are) shrink until you eventually died.

Read: “Metabolic Damage” and “Starvation Mode,” Debunked by Science

These mechanisms are why many “gurus” vilify insulin and eating carbs (because carbs spike insulin levels).

As insulin blunts fat burning and triggers fat storage, the basic theory is the more insulinogenic a diet is, the more it will cause weight gain.

This seems plausible at first blush, but it completely ignores the most important dimension of weight management:

Energy intake.

Because the reality is insulin can’t make you fat. Only overeating can.

Read: Research Review: Are Ketogenic Diets Best for Fat Loss?

The scientific underpinnings at play here are referred to as energy balance, which is the relationship between the amount of energy you expend (burn) and consume (eat).

- If you eat more energy than you burn, you’re in a state of positive energy balance, and you will gain fat.

- If you eat less energy than you burn, you’re in a state of negative energy balance, and you will lose fat.

You can get fatter eating only the “cleanest” fare and lose fat on a diet of convenience store pigswill.

These principles don’t just apply to your diet as a whole and over time—they apply to every meal you eat.

Specifically, your body is always in one of two states in relation to food:

A “fed” state.

In this state, your body is digesting, processing, absorbing, and storing nutrients from food you’ve eaten. This is when fat burning is blunted and fat stores are increased.

A “fasted” state.

In this state, your body has finished processing and absorbing (and storing) food you’ve eaten. This is when it must turn to its fat stores to obtain the energy necessary to stay alive, and hence when fat stores are decreased.

In other words, your body alternates between storing and burning fat every day, which is neatly illustrated by the following graph:

If you take a closer look at that graph, you can come to a few simple conclusions:

- If, over time, you store as much fat as you burn, then your total fat mass will stay the same.

- If you store more fat than you burn, then your total fat mass will increase.

- If you burn more fat than you store, then your total fat mass will decrease.

- When you eat more energy than you burn, the sum of the green portions of the graph outweigh the sum of the blue portions.

- When you eat less energy than you burn, the reverse is observed (the blue portions become greater than the green).

- And when you eat more or less the same amount of energy as you burn, the areas of the two portions are balanced.

We recall that TEF contributes to overall energy expenditure, which means it slightly decreases the size of the green areas of the graph (the post-meal fat storage).

That is, TEF can contribute to weight loss by increasing the amount of energy your body burns, but the magnitude of these effects is far too small to really move the needle.

You can gain weight on a diet rich in high-TEF foods because you simply eat too much of them, and you can lose weight on a diet rich in low-TEF foods because you simply know how many calories to eat and regulate your intake of them.

This is why the entire idea of “fat-burning foods” is a myth.

Summary: Energy expenditure rises when you eat food, but the magnitude is too small to significantly impact weight loss.

[h=2]The Great “Fat-Burning Food” Hoax[/h]

Fitness blogs can write all the listicles they want about which foods burn fat and which don’t, but it’s all a bunch of humbug.

It doesn’t matter how much celery or tuna you eat every day—it’s not going to noticeably decrease your fat stores unless you’re also in a state of negative energy balance (a calorie deficit).

And you now know why:

Food doesn’t burn fat. Energy expenditure does.

Thanks to TEF and other factors beyond the scope of this article, some foods result in less fat storage than others, but rest assured that an energy surplus results in some degree of fat gain regardless of the composition of your diet.

I mentioned earlier that some foods are more conducive to weight loss than others.

That is, they’re not “fat-burning foods,” but they do help you lose weight faster.

Generally speaking, foods that are “good” for weight loss are those that are relatively low in calories but high in volume (and thus satiating).

Many also have a high TEF value as well, and that’s an added bonus.

Examples of such foods include . . .

- Basically all forms of protein

- Whole grains

- Seeds and nuts (they offset at least some of their energy density with their high TEF and satiety factors)

- Many types of fruits and vegetables

Summary: There’s no such thing as a “fat-burning food,” but eating foods that are highly satiating and low in calories can help you maintain a negative energy balance, and thus lose weight over time.

[h=2]40 Foods with a High Thermic Effect[/h]While no food can “burn fat,” some foods do have a much higher thermic effect than others, and including more of these in your diet can make it slightly easier to lose weight and keep it off.

Remember that foods with minimal processing tend to have the highest thermic effect, and this is true of proteins, carbs, and fats, so you want to prioritize these in your diet to maximize TEF.

[h=3]Protein[/h]Most high-protein foods will have a thermic effect of anywhere from 20 to 35%—meaning they’re highly thermogenic. Here are some proteins with a high thermic effect:

- Chicken or turkey breast (skinless, boneless)

- Tilapia

- Chuck roast beef (or London broil)

- Eggs

- Pork tenderloin

- Mutton (fat removed)

- Tuna

- Bison

- Venison

- Cottage cheese (low-fat)

- Barley

- Oats

- Buckwheat

- Quinoa

- Bulgar wheat

- Couscous

- Rice

- Chickpea

- Kidney bean

- Pea

- Broccoli

- Asparagus

- Cauliflower

- Celery

- Lettuce

- Cucumber

- Kale

- Spinach

- Carrot

- Beetroot

- Almond

- Peanut

- Walnut

- Cashew

- Pistachio

- Avocado

- Pecan

- Pumpkin seed

- Flax seed

- Chia seed

If eating food boosts your metabolism, eating more meals should be better than fewer . . . right?

Wrong.

The flaw in this logic is the assumption that all meals result in more or less the same increase in energy expenditure.

The reality, though, is small meals result in smaller, shorter metabolic spikes, and larger meals produce larger, longer lasting effects.

And is there any benefit to one of these over the other?

That is, does eating fewer, larger meals raise your total daily TEF more than eating more frequent, smaller meals, or vice versa?

Maybe, but probably not.

Some studies show that eating fewer, large meals raises total daily TEF more than eating more frequent, smaller meals. That said, all of these studies were fairly short, didn’t involve many participants, and didn’t track body weight over time, so it’s impossible to say one method is clearly better than the other.

What’s more, many studies have shown that there’s no significant difference in total energy expenditure between “nibbling” and “gorging.”

In other words, your total daily TEF balances out to more or less the same amount regardless of how many meals you eat or how often you eat them.

Thus, the best approach is to follow the meal frequency that works best for you.

If you prefer to eat more frequent, smaller meals, go for it—and if you prefer to eat less frequent, larger meals, that’s fine, too.

The most important thing is that you follow a meal frequency that you enjoy and that helps you reliably meet your daily calorie and macronutrient targets.

Summary: You’ll burn the same number of calories from TEF throughout the day whether you eat many small meals or few large meals, so you should follow the meal frequency that you enjoy most and that helps you stick to your diet.

[h=2]Can You Do Anything to Raise the Thermic Effect of Food?[/h]So, aside from eating high-TEF foods (protein, carbs, and minimally processed foods), is there anything else you can do to raise TEF?

Yes, probably.

First, at least one study has shown that strength training can boost TEF considerably. Specifically, people who ate a 660-calorie meal experienced a 20% increase in TEF over the next two hours, whereas people who ate the same meal after lifting weights enjoyed a 34% increase in TEF—a 73% (relative) increase!

Research also shows that the lower your insulin sensitivity and the higher your body fat percentage, the lower your TEF will be. Thus, it’s possible that the reverse is also true—that improving your insulin sensitivity and reducing your body fat levels may increase your TEF.

Now, it’s still not clear if being insulin sensitive and lean causes an increase in TEF or if it’s just correlated with a high TEF (people who are lean and insulin sensitive might just happen to have a higher TEF, for example). But it’s one of the few things you might be able to do to raise TEF, so it’s worth trying (not to mention the fact that being insulin sensitive and lean confers a number of other benefits).

Read: 13 Studies Answer: What’s the Best Way to Lower Blood Sugar?

There’s nothing you can do to automagically boost your insulin sensitivity or reduce your body fat percentage, but you can improve both significantly by exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet.

So, if you want to increase the amount of energy your body uses to digest food, the best way to do so is by doing a few hours of strength training and cardio each week, and eat a calorie-controlled and nutritious diet.

Summary: You can increase TEF by lifting weights and possibly also by improving your insulin sensitivity and reducing your body fat percentage, which you can do by staying active and maintaining a calorie deficit.

[h=2]The True Benefits of a Highly Thermogenic Diet[/h]We’ve covered a lot of ground already, but I want to touch on one last subject before signing off.

And that’s the reality that while TEF isn’t terribly important in the overall scheme of losing fat, the best type of diet for weight loss is highly thermogenic.

We recall that protein, carbs, and fats affect the metabolism in different ways. They have different TEF values and they are processed and stored differently.

For example, high-protein and high-carb meals cause a bigger metabolic boost and result in less immediate fat storage than high-fat meals.

It’s not surprising, then, to learn that research shows that high-protein, high-carb diets (which are highly thermogenic) are best for maximizing fat loss.

There are several reasons for this:

- Protein and carbs have a higher thermic effect than fats, which bolsters daily energy expenditure.

- Protein and carbs are generally more filling than fats, which helps prevent overeating.

- Eating adequate protein and carbs while dieting for fat loss helps preserve lean mass, which in turn helps maintain a healthy metabolism.

If you’re healthy and physically active, a high-protein, moderate-to-high-carb, and moderate-to-low-fat intake is generally going to be best.

(If that sounds ludicrous to you, check out this article on the big myths surrounding low-carb and high-fat dieting.)

Summary: A high-protein, moderate-to-high-carb, and moderate-to-low-fat diet is the best kind of weight loss diet for most people, and it happens to be highly thermogenic.

[h=2]The Bottom Line on the Thermic Effect of Food[/h]You can’t lose weight faster by eating more frequently, gorging on thermogenic foods, or doing anything other than maintaining a calorie deficit.

That said, getting a larger portion of your daily calories from foods that have a higher TEF like minimally processed lean proteins, vegetables, and whole grains can make it slightly easier to lose weight and keep it off.

What’s more, there’s good evidence that strength training can also amplify the thermic effect of food.

Practically speaking, though, your primary concern when trying to lose weight should be meeting your daily calorie and macronutrient targets and eating a plant-centric, whole foods diet. Luckily, this kind of diet also happens to be highly thermogenic.

In other words, when you eat a high-protein, moderate-to-high-carb, and moderate-to-low-fat diet made up of mostly whole foods, you’re going to reap all the benefits of the thermic effect of food automatically.

One more reason to focus on the fundamentals.

If you liked this article, please share it on Facebook, Twitter, or wherever you like to hang out online!

[h=3]What’s your take on the thermic effect of food? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below![/h]The post How to Use the Thermic Effect of Food to Boost Your Metabolism appeared first on Legion Athletics.

{feed:enclosure_href }

More...