[FONT="][h=1]Improve Your Lats For That V-Taper...

By: Zack Trowbridge

[/h][/FONT]

[/h][/FONT]

[FONT="]One of the hardest parts of developing your back is how difficult it can be to get the stress in the intended area. Too much trap involvement in your rows, too much biceps on your pullups — it’s an area that’s made all the more complicated by the fact that you can’t even see what you’re training, which means you have to learn to go by feel. Textbook form or not, nothing is going to grow unless you can get your mind and muscle to link up and work together.

I struggled with this for a long time. Even though I was using what could be considered extremely technically sound program design and had been told by more than a few coaches that my lifting technique was good, I still struggled to make improvements. It wasn’t until I really started to develop a bit of a love for anatomy and biomechanics (trust me, they’re more fun than they sound) that things started to take off. Little, slight tweaks to my execution suddenly made a good movement into a great one, even if it initially cost me significant poundage on the bar — which, by the way, is something that you should be okay with. You can grow your muscles or you can grow your ego, but most of the time those two things tend to be mutually exclusive.

I had made my back a significant priority over the last 12 months as I had seen the pictures from my last contest and was not pleased with how I compared to the other athletes on stage. I trained it consistently 2-3 times per week for close to a year to give it the stimulus it needed, but more importantly, I was paying extra attention to which parts of my back were working and how I could manipulate the outcome of a particular set by concentrating on different things. This step, combined with lots of hard work and consistency, seems to have paid off.

I began using John Meadows' training programs in September 2015, and signed on as a client with John and Cris Edmonds in March of 2016. For almost that entire time period, bringing up my back was a large priority before stepping on stage again. It was hit twice a week with a combination of the traditional heavier Mountain Dog-style base days, and an added high-volume pump day to help ramp up the total training volume per week. Cris and John also helped me figure out tweaks to my movement execution that kept the stress entirely where it was intended to be.

Part of that strategy was using what some people might refer to as “activation” movements, but a better way to look at it would simply be to call them movements that don’t allow for a lot of gray area. Either you’re doing them right or you’re not. They don’t allow for a lot of weight to be used, as the goal is simply to isolate a particular aspect of the back’s anatomy and then carry that feeling over into the rest of the workout. These three movements are ones that I found to be particularly effective. I’ve included some of the ways that they can be applied in the context of an overall training plan.

[h=2]Scarecrows[/h]I wish for the life of me that I could give credit to the right person for this movement, but I cannot remember where I got the idea for these. I do remember that the version I first saw used dumbbells to create resistance, but I’ve had much better success using these with myself and my clients by using a small band, especially when the goal is to use the scarecrow to precede a big compound movement.

These tend to really light up the upper back. I have found that it is very helpful to place several very slow, controlled reps before bigger movements like elbows-out barbell/dumbbell rows or wide grip pulldowns — or really any movement you can perform with the elbows positioned quite wide and the emphasis placed on a hard retraction of the scapulae.

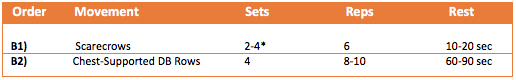

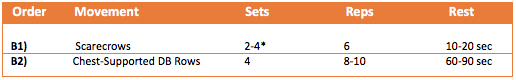

[FONT="]Sample placement:

*Use as needed. If your upper back is lighting up after a few sets, you don’t need to continue with them beyond that point. The goal should be to make the B2 exercise better, not to fatigue you so hard that it takes away from it.

You may notice that this particular example is placed later in the workout (B1 and B2) instead of at the beginning. My personal preference at this point is to have a back workout start with a very lat-driven exercise. I’m sure this has a lot to do with John Meadows’ programming, which usually leads off with things like bentover rows, Meadows rows, one-arm barbell rows, or one-arm lat pulldowns before progressing to more isolated upper back work. If it isn’t broken, I’m not about to try to fix it.

[h=2]Straight-Arm Dumbbell Rows[/h]One of my favorite lat movements is the straight arm rope pulldown performed with a high cable pulley. However, for a long time I didn’t belong to a commercial gym and was doing all of my training exclusively at All Strength Training, the personal training studio that my wife and I own. During this time we didn’t have any options for cable exercises, so I improvised and started using these a lot in my training.

One thing I do like about these compared to straight arm pulldowns is that they only work the top 30-40% of the range of motion. That might sound like a bad thing, but when the focus is simply on getting the lats to fire up, I do like keeping the range of motion from getting too large; if you’re not great at placing stress in the right place, it’s too easy to start inviting momentum and other muscle groups to get involved.

I also prefer to use them with chest support on an incline bench to eliminate any lower back contribution. Doing them without the chest support would make the contraction more intense if you can get your torso set at parallel to the floor and can do them without momentum.

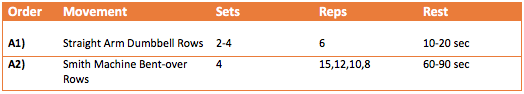

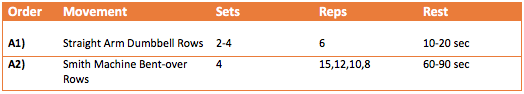

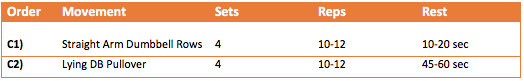

[FONT="]Sample placement:[/FONT]

It doesn’t take a lot of weight to get these going, and the goal isn’t to get them high and behind you, but to treat it like you’re trying to drag them along the floor and then push them back toward your heels (or the wall behind you, if you’re in a fully bent over position).

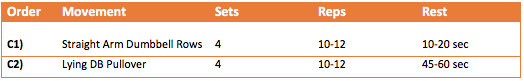

They can also be placed as a superset with traditional lying dumbbell pullover to cover both ends of the strength curve — one picks up where the other leaves off.

You’ll notice these are positioned a bit later in the workout, with higher reps and shorter rest intervals. If I was going to superset these two, I would put them after my heavier work and use them to drive a huge pump in the lats followed by a big stretch with pullovers.

[h=2]Bench Thoracic Extensions[/h]My original exposure to these was through a movement I learned here on elitefts.com called the Upper Back Shrug, which requires an SS Yoke Bar. We do have an SS Yoke Bar at AST, but since I’m doing most of my training now at Lifetime Fitness (hey, if you were an accountant all day long, would you really stay in your office when it’s time to do your own taxes?), I’ve had to improvise.

I saw a video from powerlifter Matt Wenning demonstrating something similar but instead using a flat bench. The only issue I’ve had with trying to get some of my clients (and myself) doing them that way is that if the thoracic extensors are weak to begin with, there is a tendency to compensate with the lower back and go into lumber extension instead of thoracic extension. Starting with an inclined bench decreases the amount of your bodyweight you have to lift and you can always move on to a flat bench once you have the strength and technique to do so.

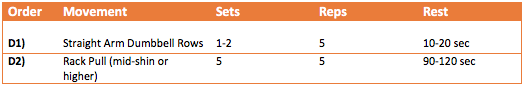

I have tried these placed in front of both lat pulldowns and deadlifts/rack pulls. Pretty polar opposite movements, but both have been known to get people arching their lower backs excessively at the end of the movements when the goal should be to get the head lifted as high as possible and the spine as lengthened as possible in the contracted position. I remember the first time I got this correct and my mid-back (lower traps, lower lats, upper erectors) was absolutely demolished. I personally don’t even like adding weight to them, although you certainly could with a dumbbell held at the chest or positioned behind the head. I like to do 5-6 reps when I need to get my mind right for the lift that follows.

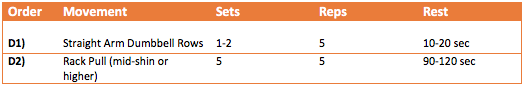

Unlike the other movements, I actually prefer to put these in front of my last set or two instead of the earlier sets, as it works as a good reminder of what I should be doing when fatigue is starting to build, particularly with a movement like the rack pull. Again thanks to John Meadows, I’ve developed a love for doing rack pulls last or close to last on back day when the weight can’t be as heavy and everything else is already trashed.

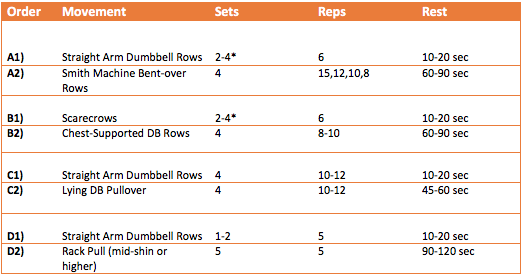

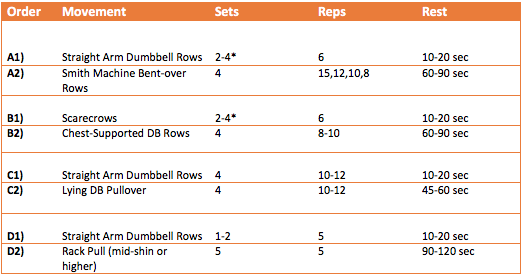

[FONT="]If you put all of this together, the whole day would look like this:[/FONT]

Happy lifting, and enjoy the DOMS!

[/FONT]

[/FONT]

By: Zack Trowbridge

[FONT="]One of the hardest parts of developing your back is how difficult it can be to get the stress in the intended area. Too much trap involvement in your rows, too much biceps on your pullups — it’s an area that’s made all the more complicated by the fact that you can’t even see what you’re training, which means you have to learn to go by feel. Textbook form or not, nothing is going to grow unless you can get your mind and muscle to link up and work together.

I struggled with this for a long time. Even though I was using what could be considered extremely technically sound program design and had been told by more than a few coaches that my lifting technique was good, I still struggled to make improvements. It wasn’t until I really started to develop a bit of a love for anatomy and biomechanics (trust me, they’re more fun than they sound) that things started to take off. Little, slight tweaks to my execution suddenly made a good movement into a great one, even if it initially cost me significant poundage on the bar — which, by the way, is something that you should be okay with. You can grow your muscles or you can grow your ego, but most of the time those two things tend to be mutually exclusive.

I had made my back a significant priority over the last 12 months as I had seen the pictures from my last contest and was not pleased with how I compared to the other athletes on stage. I trained it consistently 2-3 times per week for close to a year to give it the stimulus it needed, but more importantly, I was paying extra attention to which parts of my back were working and how I could manipulate the outcome of a particular set by concentrating on different things. This step, combined with lots of hard work and consistency, seems to have paid off.

I began using John Meadows' training programs in September 2015, and signed on as a client with John and Cris Edmonds in March of 2016. For almost that entire time period, bringing up my back was a large priority before stepping on stage again. It was hit twice a week with a combination of the traditional heavier Mountain Dog-style base days, and an added high-volume pump day to help ramp up the total training volume per week. Cris and John also helped me figure out tweaks to my movement execution that kept the stress entirely where it was intended to be.

Part of that strategy was using what some people might refer to as “activation” movements, but a better way to look at it would simply be to call them movements that don’t allow for a lot of gray area. Either you’re doing them right or you’re not. They don’t allow for a lot of weight to be used, as the goal is simply to isolate a particular aspect of the back’s anatomy and then carry that feeling over into the rest of the workout. These three movements are ones that I found to be particularly effective. I’ve included some of the ways that they can be applied in the context of an overall training plan.

[h=2]Scarecrows[/h]I wish for the life of me that I could give credit to the right person for this movement, but I cannot remember where I got the idea for these. I do remember that the version I first saw used dumbbells to create resistance, but I’ve had much better success using these with myself and my clients by using a small band, especially when the goal is to use the scarecrow to precede a big compound movement.

These tend to really light up the upper back. I have found that it is very helpful to place several very slow, controlled reps before bigger movements like elbows-out barbell/dumbbell rows or wide grip pulldowns — or really any movement you can perform with the elbows positioned quite wide and the emphasis placed on a hard retraction of the scapulae.

[FONT="]Sample placement:

*Use as needed. If your upper back is lighting up after a few sets, you don’t need to continue with them beyond that point. The goal should be to make the B2 exercise better, not to fatigue you so hard that it takes away from it.

You may notice that this particular example is placed later in the workout (B1 and B2) instead of at the beginning. My personal preference at this point is to have a back workout start with a very lat-driven exercise. I’m sure this has a lot to do with John Meadows’ programming, which usually leads off with things like bentover rows, Meadows rows, one-arm barbell rows, or one-arm lat pulldowns before progressing to more isolated upper back work. If it isn’t broken, I’m not about to try to fix it.

[h=2]Straight-Arm Dumbbell Rows[/h]One of my favorite lat movements is the straight arm rope pulldown performed with a high cable pulley. However, for a long time I didn’t belong to a commercial gym and was doing all of my training exclusively at All Strength Training, the personal training studio that my wife and I own. During this time we didn’t have any options for cable exercises, so I improvised and started using these a lot in my training.

One thing I do like about these compared to straight arm pulldowns is that they only work the top 30-40% of the range of motion. That might sound like a bad thing, but when the focus is simply on getting the lats to fire up, I do like keeping the range of motion from getting too large; if you’re not great at placing stress in the right place, it’s too easy to start inviting momentum and other muscle groups to get involved.

I also prefer to use them with chest support on an incline bench to eliminate any lower back contribution. Doing them without the chest support would make the contraction more intense if you can get your torso set at parallel to the floor and can do them without momentum.

[FONT="]Sample placement:[/FONT]

It doesn’t take a lot of weight to get these going, and the goal isn’t to get them high and behind you, but to treat it like you’re trying to drag them along the floor and then push them back toward your heels (or the wall behind you, if you’re in a fully bent over position).

They can also be placed as a superset with traditional lying dumbbell pullover to cover both ends of the strength curve — one picks up where the other leaves off.

You’ll notice these are positioned a bit later in the workout, with higher reps and shorter rest intervals. If I was going to superset these two, I would put them after my heavier work and use them to drive a huge pump in the lats followed by a big stretch with pullovers.

[h=2]Bench Thoracic Extensions[/h]My original exposure to these was through a movement I learned here on elitefts.com called the Upper Back Shrug, which requires an SS Yoke Bar. We do have an SS Yoke Bar at AST, but since I’m doing most of my training now at Lifetime Fitness (hey, if you were an accountant all day long, would you really stay in your office when it’s time to do your own taxes?), I’ve had to improvise.

I saw a video from powerlifter Matt Wenning demonstrating something similar but instead using a flat bench. The only issue I’ve had with trying to get some of my clients (and myself) doing them that way is that if the thoracic extensors are weak to begin with, there is a tendency to compensate with the lower back and go into lumber extension instead of thoracic extension. Starting with an inclined bench decreases the amount of your bodyweight you have to lift and you can always move on to a flat bench once you have the strength and technique to do so.

I have tried these placed in front of both lat pulldowns and deadlifts/rack pulls. Pretty polar opposite movements, but both have been known to get people arching their lower backs excessively at the end of the movements when the goal should be to get the head lifted as high as possible and the spine as lengthened as possible in the contracted position. I remember the first time I got this correct and my mid-back (lower traps, lower lats, upper erectors) was absolutely demolished. I personally don’t even like adding weight to them, although you certainly could with a dumbbell held at the chest or positioned behind the head. I like to do 5-6 reps when I need to get my mind right for the lift that follows.

Unlike the other movements, I actually prefer to put these in front of my last set or two instead of the earlier sets, as it works as a good reminder of what I should be doing when fatigue is starting to build, particularly with a movement like the rack pull. Again thanks to John Meadows, I’ve developed a love for doing rack pulls last or close to last on back day when the weight can’t be as heavy and everything else is already trashed.

[FONT="]If you put all of this together, the whole day would look like this:[/FONT]

Happy lifting, and enjoy the DOMS!

[/FONT]

[/FONT]