By the numbers, weightlifting is thriving: The 2023 World Weightlifting Championships hosted more competitors than in any year prior. A few weeks after that, Bulgarian prodigy Karlos Nasar set social media ablaze with his 223-kilogram clean & jerk world record at the IWF Grand Prix II. An Instagram post documenting the lift has since racked up well over 20 million views — not a bad haul for a small sport. And the 2024 Olympics are on the horizon.

But if you’re a fan, watching weightlifters perform with the barbell over the last two-ish years has been a mixed bag. While there are certainly moments of fist-pumping, stadium-thumping exhilaration, you’d be hard-pressed to find those Nasarish thrills in, like, half of all of weightlifting’s classes in 2024.

There’s a talent drought plaguing parts of the sport, while athletes in the “Paris categories” are producing either the snooziest or most awe-inspiring lifting you can imagine. And the pathway to the 2024 Olympics, once assumed to be weightlifting’s swan song at the Games, is at least partly to blame.

[Related: 2024 IWF World Cup Preview]

How an Athlete Gets to Paris (2024)

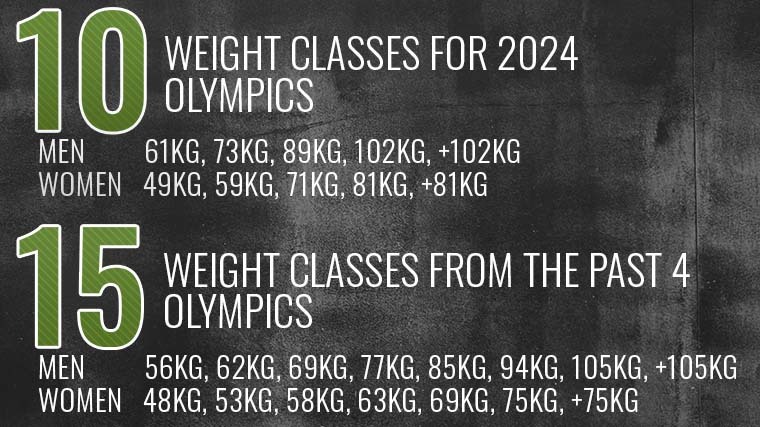

Since 2012, weightlifting’s presence at the Olympic Games has diminished, and diminished, and diminished. Cuts to athlete quotas — and even the excision of entire weight classes — are among the sanctions levied by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) toward the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) for its ineffectual approach to policing performance-enhancing drug use.

At the 2012 Olympic Games in London, 260 weightlifters performed on stage across 15 weight classes. In Paris, 120 athletes will compete in 10 weight classes. There will be fewer weightlifters in Paris than at any Games since 1956.

“The best weightlifters in the world all want to go to the Olympics,” says Seb Ostrowicz, founder of Weightlifting House, whose media outfit broadcasts international weightlifting events on behalf of the IWF. “They’ll find a way to gain or lose the weight to get into an Olympics class if they have to.”

When the Paris classes were confirmed in early 2022, Olympic hopefuls began migrating out of their “home” divisions and into the ones that will be held in Paris, like the Men’s 89-kilogram, where Nasar currently reigns.

And while a fan of weightlifting can get to Paris with a plane or train ticket, career weightlifters need to:

- Attend five major international competitions, including two specific mandatory events.

- Rank in the top 10 in the world in a Paris-recognized weight class when the qualification period concludes in late spring.

Weightlifting hasn’t had such a straightforward pathway to the Olympics in its modern history. There are technicalities and nuances to the rules, but all a weightlifter really needs to secure their slot in Paris is one damn-good day on the platform.

[Related: Why Can’t North Korea Compete in Weightlifting at the 2024 Olympics?]

There Are Too Many Bomb-Outs…

At a glance, you might think that such a do-or-die qualification system would make weightlifting more fun to watch, and it has — at a cost. “The Olympic categories have, at their best, world records. At their worst, there are more bomb-outs than anyone has ever seen, and there’s not much in between,” says Team USA athlete and 2021 World Champion Meredith Alwine. “Medals are irrelevant.”

Instead of cultivating a fiery, competitive atmosphere at big meets, the Paris system incentivizes countries to send their would-be Olympians to weigh in, take one or two shots at a big Total, and pay little heed to much else.

A bomb-out occurs when an athlete fails to register a Total; the sum of their heaviest snatch and clean & jerk.

Not every country has embraced the go-big-or-go-home game plan to the same degree, but Ostrowicz notes that it is the prevailing strategy for teams like Italy:

“The Italians open too heavy, in many cases … they’re super aggressive with their attempt selection. They load what they need to break into the top 10, try to lift those numbers, rinse, and repeat.”

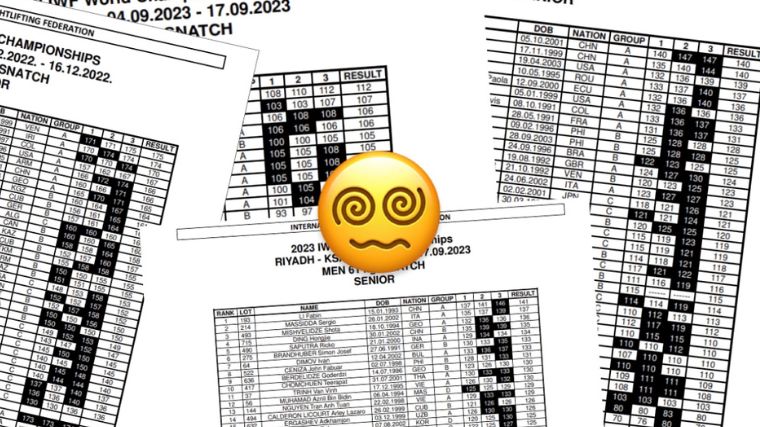

At the 2022 World Championships, the Italians only registered 13 successful lifts out of 42 attempts. Flash forward to 2024, and weightlifting scoreboards all over the world are running red as athletes make desperate bids to secure their Olympic slots.

This big-Total-or-nothing approach isn’t how weightlifting teams have historically approached important competitions. Coaches and athletes alike regard a “six-for-six”, no-miss performance as the gold standard because it builds confidence and consistency, which mattered more in years past.

It’s disheartening to attend (or watch online) a big weightlifting event to support your favorite athlete, only to watch them bomb out during snatches and then withdraw before clean & jerks even begin.

Sportsmanship is upheld better in the non-Olympic categories…

This phenomenon is only worsening as the path to Paris narrows. At this year’s Asian Championships in the Men’s 102-kilogram division, only eight out of 39 clean & jerks were successful. The athletes aren’t to blame — they’re playing a high-stakes card game as efficiently as possible. Go all in or fold.

Some weightlifters thrive under this sort of pressure, but Alwine isn’t pleased by the impact the Paris qualification system has had on prestige competitions. “Who wants to watch half a session bomb because they’re opening with as much weight as they’ve ever lifted?” she remarks.

“Sportsmanship is upheld better in the non-Olympic categories, where placement and medals still matter.”

[Related: 5 of the Best Weightlifting Battles of All Time]

…And Too Few Competitive Weight Classes

The IWF and IOC playing Jenga with the sport’s bodyweight categories, plugging some in and pulling others out between every Games, sucks bigtime for the athletes and for the fans who show up to watch 100% of a competition, not half of one.

In the year-ish before the Paris Games, half of all weightlifting’s divisions have become graveyards of talent as athletes congregate in the 10 Olympic classes. Some competitors lose more weight than they’d like; others struggle to bulk up. For fans who follow weightlifting events from start to finish, it’s become feast or famine.

During the 2024 Asian Weightlifting Championships, the 55-kilogram classes (for both men and women) had only five Group A entrants each. Neither class will be showcased in Paris.

There’s also a gulf between the capabilities of athletes in the Paris classes and the non-Paris classes. At last year’s World Championships, Women’s 87-kilogram gold medalist Lo Ling-Yuan Totaled 36 kilograms less than the 81-kilogram winner, Liang Xiaomei, even though heavier athletes are almost always stronger than lighter ones in absolute terms.

This kind of thing is happening in both Women’s and Men’s weightlifting. Two of the best 109-kilogram men in the world, 2020 Olympic Champion Akbar Djuraev and two-time (2018, 2019) World Champion Simon Martirosyan, are making Paris runs in the 102s and +109s, respectively.

Want to see a new Men’s 109-kilogram world record after three years of its best performers abandoning the class? Fat chance:

The winning 109-kilogram Total at Worlds in 2023 was 415 kilograms, five years after Martirosyan set the world record with 435. Unless the 109s are elected for the 2028 Olympics, nobody is touching his record.

At the 2023 World Championships, no women’s gold medalist in a non-Paris category lifted more than their adjacent Paris-recognized counterpart, even when they weighed more.

So for fans who yearn to see history made and world records fall, what’s the incentive to keep up with a non-Paris-recognized weight class? Unless your favorite weightlifter is sticking it out in the Women’s 64s or Men’s 96s, there really isn’t one. It’s like going to the NFL playoffs and then watching an AFL game right after. If you like football, it’s still football, but seeing the two games back-to-back is deflating.

[Related: How an Unexpected Phone Call Might Get 36-Year-Old Caine Wilkes Back to the Olympic Games]

Bright Spots & a Brighter Future?

The IWF and IOC have done weightlifting — athletes and fans alike — a disservice with the Paris qualification system. Instead of the world’s best weightlifters spreading evenly across a range of body weights, they corral into the few categories allowed at the Olympics.

In the Games categories, spectators are treated to bold but reckless lifting, plenty of pre or mid-competition withdrawals (since all you have to do to “attend” an IWF qualifier is weigh in and not even pick up a barbell), and fewer white lights.

In the non-Games divisions, there’s still plenty of good lifting for diehard fans. But the bleak bit is you probably won’t see a new world record in the Women’s 55-kilogram or Men’s 96-kilogram anytime soon — unless the IOC decides to showcase those events in 2028.

Still, there are bright spots in the murk. Ostrowicz notes that the current Olympic qualification procedure means that fans tend to see their favorite athletes compete more regularly than in years past, though “…it comes at the cost of them not necessarily putting up their best performance.”

And to its credit, the Paris system is digestibly straightforward. Viewers can appreciate the stakes when they’re at their highest: Moments when an athlete must throw themselves under that third snatch or clean & jerk to make the exact Total they need to realize their Olympic dreams.

[Related: The Best Pre-Workout Supplements You Can Buy]

After the Olympic torch is doused in Paris, the IWF, once again, has its work cut out. If more of the sport is to be worth watching, more weight classes need to be confirmed for the next Olympics. For that to happen, the IWF brass must continue the bureaucratic momentum they’ve built in recent years.

But until then, anyone who supports weightlifting as a spectator must be prepared to support all of its athletes, not just the Karlos Nasars of the world who ink fresh records on a regular basis. The non-Paris classes still put on good sportsmanship, even if the weights lifted are a bit underwhelming.

Bottom line; there’s more weightlifting now than ever before, and more weightlifting is better than less. But it’s not all of the same quality. And the fans, whose devotion buoys the sport in the first place, are the ones ultimately stuck holding weightlifting’s (mixed) bag.

Editor’s Note: BarBend is the Official Media Partner of USA Weightlifting. The two organizations retain editorial independence unless otherwise specified on specific content projects.

Featured Image: Prostock-studio / Shutterstock

The post Opinion: The Sport of Weightlifting Sucks to Watch in 2024 appeared first on BarBend.